About a decade ago it was first proposed that the tight interaction between the nuclear genes, and the mitochondrial genes might play an important role in the process of speciation, contributing to patterns of geneflow across closely related species where they are in contact with each other. We were inspired to work in this area by Paul Sunnocks’ work on the eastern yellow robin, and Geoff Hill‘s excellent book ‘Mitonuclear Ecology.

Our first major paper testing these ideas has just been published in Molecular Ecology, and was part of Callum McDiarmid’s PhD thesis work (link to paper).

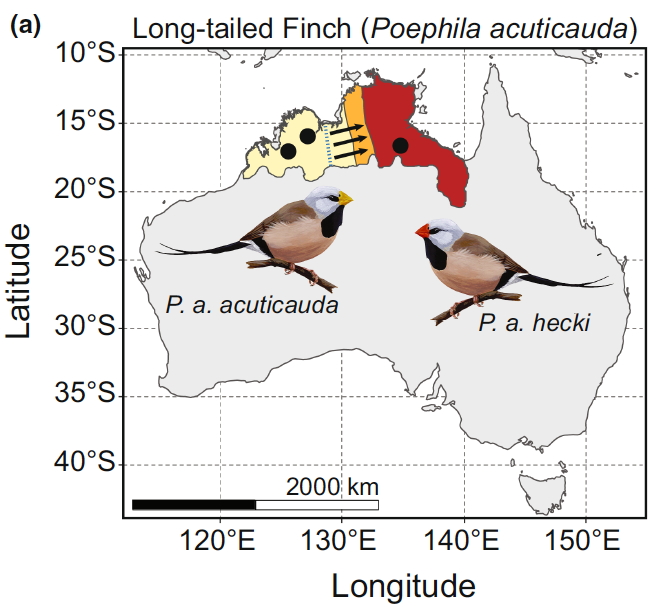

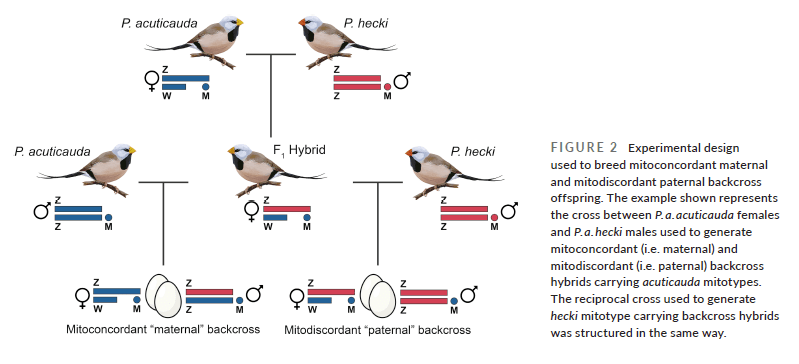

Our study was built on an amazing pre-existing knowledge of the highly conserved nuclear and mitochondrial genes that are largely shared across eukaryotes, and help to drive the operation of the mitochondria in cells, that produce most of the cellular energy. In birds 37 genes in the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) work closely with around 1,500 nuclear genes. This prior knowledge allowed us to characterise the differences between the two subspecies of long-tailed finch that we have been working on in the wild and laboratory for many years. The yellow-billed (acuticauda) and red-billed (hecki) subspecies last shared a common ancestor around 0.5 million years ago.

Due to the well-worked genetics of mitochondrial respiration in birds and other organisms, and the genomic sequencing that Daniel Hooper has been leading in the long-tailed finch as part of our collaboration, we were able to ascertain that there were fixed differences in just 0.9% of the sequence of the protein-coding genes between the two sub-species. There were also fixed differences in non-coding regions, that could effect the transcription, translation, or replication of mtDNA.

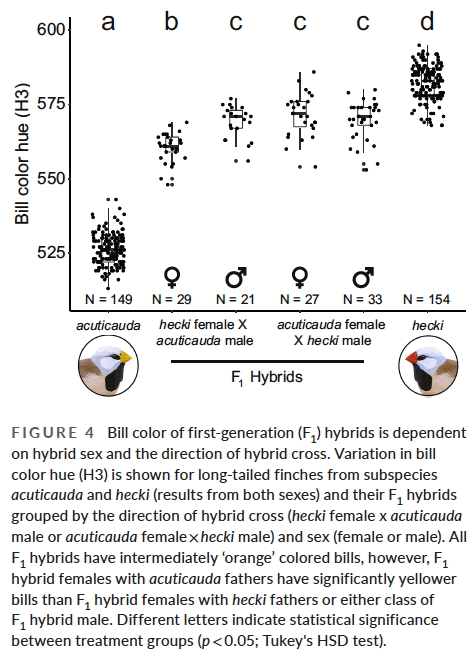

An organisms mitochondrial DNA is inherited only from it’s mother, and this allowed us to generate experimental offspring in the laboratory in which the mtDNA was in the wrong nuclear genetic background. This was done by first breeding F1 hybrid offspring – produced with either a yellow mother and red father, or vice versa. In these F1 hybrids, the mtDNA matches the sex chromosome (ZZ in males and ZW in females) that was inherited along with the mitochondria from the mother. Crucially however, when we backcross female hybrid offspring to a parental type male (paternal backcross) the mitochondrial DNA end up in the ‘wrong’ genetic background.

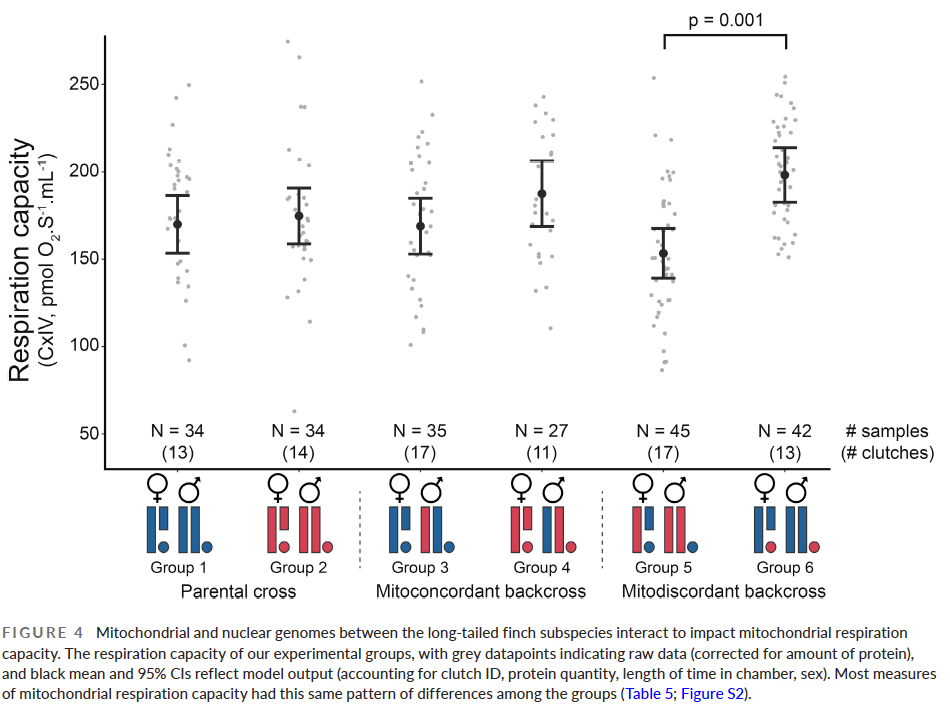

Using this experimental design we tested for functional effects of mitodiscordance (i.e. when mitochondrial DNA does not perfectly match nuclear DNA), using an Oroboros oxygraph machine to measure cellular respiration in cells from the different crosses. This machine can effectively measure the respiration capacity – the ability of an organism to make the cellular energy that fuels all growth, movement and cellular activity.

Our key findings were that we found a significant difference in the respiration capacity (the ability of an organism to make the cellular energy that fuels all growth, movement and cellular activity) of the two different types of mitodiscordant crosses, but not between those and other types of cross, like those between pure parental types (see the difference between Group 5 and 6 below).

The difference between these two mitodiscordant backcrosses that we have demonstrated using a careful experiment in the laboratory is entirely consistent with the pattern of admixture in the wild. Group 5 here are individuals with acuticauda mtDNA in an otherwise hecki genome, while Group 6 individuals have hecki mtDNA in an acuticauda genome. The acuticauda mitotype therefore performs relatively poorly in the wrong background, compared to the hecki mitotype. The two subspecies are in contact in the wild, and we have found that 83% of those individuals that have mismatched mtDNA and nuclear genome in the wild have the hecki mitotype (i.e. as we have shown experimentally, that mitotype performs better when in the wrong background). Secondly, in the wild the contact zone between the subspecies is slightly complicated with the cline of mtDNA displaced about 55km to the west of the nuclear DNA cline. i.e. the hecki mtDNA is able to move further westwards, presumably because it performs better than the acuticauda mitotype in the zone of mixed genomes.

In summary, whilst there is a relatively low level divergence between the mitochondrial DNA of the two subspecies that we have been studying in northern Australia, using experimental crosses in the laboratory, coupled with a sophisticated method for measuring the efficiency of cellular respiration, we have been able to show how functional differences can effect the introgression of genes from one from into another when species come together in secondary contact. Our findings from a bird add to recent work on other animals that support the idea that interactions between the mitochondrial and nuclear genomes can play important roles in the speciation process.